Nillofar Beyzaie, (playwright, director, critic)

نیلوفر بیضایی

بهرام بیضایی، نابغه ی خودساخته و تلاشگر خستگی ناپذیر فرهنگ و هنر ایران

در این سخنرانی ضمن نگاه کوتاهی به زندگینامۀ بهرام بیضایی به عنوان پشتوانۀ آثار هنری اش، به ویژگیهای آثار او خواهم پرداخت. شناخت عمیق او از فرهنگ، اساطیر و همچنین تاریخ ایران و در عین حال تحقیقات پیگیر او در مورد شیوه های نمایشی در ایران و شرق او را به ایرانی ترین هنرمند اندیشه ورز عرصه ی تئاتر و سینمای ایران بدل کرده است. او ضمن تکیه بر این شناخت، موفق به نو آوری، گسترش این امکانات و خلق آثار چند لایه شده است که با ذکر چند نمونه از میان آثارش بدان خواهم پرداخت.

نیلوفر بیضایی، نمایشنامه نویس و کارگردان تئاتر است. او متولد سال ١٣٤٥ در تهران است. در سن هجده سالگی ناچار به ترک ایران شد و در شهر فرانکفورت به تحصیل در رشته های ادبیات آلمانی، تئاتر- سینما و تلویزیون و تعلیم و تربیت پرداخت. در سال ١٣٧٣ از دانشگاه گوته ی فرانکفورت با مدرک کارشناسی ارشد فارغ التحصیل شد و در همانسال گروه تئاتر “دریچه” را در این شهر بنیانگذاری کرد. نیلوفر بیضایی علاوه بر کارگردانی و نمایشنامه نویسی، طراحی صحنه، لباس و نور اکثر کارهای خود را نیز بر عهده داشته است. نمایشنامه های او علاوه بر فرانکفورت با بیش از دویست اجرا در بسیاری از شهرهای دیگر آلمان ، اروپا ، کانادا و آمریکا به نمایش در آمده اند. گروه تئاتر دریچه با تولید بی وقفه ی تئاتر در دو دهه ی گذشته یکی از پرکارترین گروههای تئاتر ایرانی در خارج از کشور بوده است. او علاوه بر نمایشنامه نویسی و کارگردانی تئاتر، مقالات تخصصی در زمینه ی تئاتر ، سینمای ایران و ادبیات آلمان نوشته است. وی همچنین مطالب متعددی در مورد موضوعات اجتماعی و سیاسی مربوط به ایران نوشته که درنشریات خارج از کشور به چاپ رسیده است.

نیلوفر بیضایی در سال ١٣٨٤ جایزهٔ آکادمی ایرانی هنر،ادبیات و رسانه در بوداپست را در رشتهٔ هنرهای نمایشی بعنوان بهترین کارگردان از آن خود کرد. لیست نمایشهایی که تاکنون به کارگردانی نیلوفر بیضایی به صحنه رفته است

بانو در شهر آينه (1995)، مرجان، ماني و چند مشكل كوچك (1997-1996)، بازي آخر (1998-1997)، سرزمين هيچكس (1999-1998)، بی نام ( یک پرفرمنس بدون کلام بر اساس خاطرات زندان شهرنوش پارسی پور، 1998)، چاقو در پشت (2000-1999)، روياهاي آبي زنان خاكستري (2001-2000)، سه نظر درباره ي يك مرگ (2002-2001)، بوف كور (فارسی 2005-2004 (، بوف كور (اجراي دو زبانه فارسي – آلماني، 2005)، دختران خورشيد درچارچوب پروژه ی نمایشی“ نه بهشت، نه جهنم“ گروه تئاتر مارالام- سوئيس بزبان آلمانی (2005)، بیگانه چون من و تو (بزبان آلمانی/2006)، آوای سکوت (بزبان آلمانی/2007)، سرزمین هیچکس (بزبان آلمانی در فستیوال هزار و یک ایران در تئاتر شهر کارلسروهه، 2009)، یک پرونده، دو قتل (2010-2009) چهره به چهره در آستانه ی فصلی سرد (2011-2010)، از میان کابوسها یا چگونه انقلاب نوه هایش را نیز بلعید (2011، روخوانی نمایشی بزبان آلمانی، اجرا شده در تئاتر شهر فرانکفورت در چارچوب پنجاهمین سالگرد سازمان عفو بین الملل)، در حضور باد (2016-2015)

Email: [email protected]

*****************************

Hamid Ehya (director, actor and translator)

زبان و شکلهای نمایشی در طرب نامه

ارزش و شکوه زبان در آثار بیضایی بر هیچ کس پوشیده نیست. اما زبان طربنامه شگفت انگیز است. بیضایی با این تخت حوضی یک بار دیگر ثابت می کند که استاد زبان است؛ استادِ دانا و هنرمند و چیره دستی که با زبان تردستی می کند. زبان این اثر نه ساعته، با داستانهای هزار تو و هزار و یکشبی خود، پویا زبانی است متنوع، زنده و جاندار، جذاب و از همه مهمتر نمایشی. نوشته ی حاضر تلاش می کند که با ارائه ی نمونه هایی از متن، گستردگی، تنوع، زیبایی، و ارزش و اهمیت این زبان را نشان دهد؛ رابطه ی آن را با شکهای گوناگون نمایشی ایران مشخص کند، و به بررسیِ عناصری که آن را نمایشی می کنند بپردازد

Hamid Ehya studied theater at Tehran University and received his MA in Performance Studies from New York University. He is a published theater translator and his writings have appeared in a number of Persian theater journals. In 2009, his translation of Copenhagen won the ‘best translation of the year’ award from the Iranian Playwrights Association. Ehya has worked with Darvag Theater Group as a director, actor, and translator since 1985. In 2015 he appeared in prof. Beyzaie’s Ardaviraf’s Repor’ and in 2016 he played PirPoosh in Tarabnameh.

*********************************

Maryam Ghorbankarimi, PhD in Film Studies, University of St Andrews

Captive Bodies Buried in Oblivion: Female Identity in Beyzaie’s Downpour (1972)

In the aftermath of World War Two the Iranian film industry began making films with song and dance scenes in an attempt to imitate popular Egyptian and Indian films. These melodramas now known under the umbrella title of film farsi portrayed a very stereotypical, binary image of women: a woman was either entirely good or bad. However, the popularity of these films pushed the film industry closer towards producing purely entertaining films, while the independent cinema was also born along side this popular trend as a counter movement.

The 1960s mark the birth of the Iranian New Wave and the breaking away from commercialism. Films became the subject of intellectual debates as some of them were politically charged, while for the most part they followed the film farsi style. The character of the luti, the protagonist of the film farsi genre, usually a macho who takes the law into his own hands, embodied the political struggle of working class people with the system. Lutis gained their self-respect by fighting both, the tyrant and the Westernized rich, while remembering the poor and those in need.

Although these films were targeting the middle-class intellectuals of Iran rather than the working class, in comparison with the films of the preceding years they were not offering an improvement in their representation of women. One major exception in this regard is Bahram Beizai’s Downpoor (Ragbār, 1972). Although it shares the general characteristics of its zeitgeist with other films, this paper will offer a close reading of it with a focus on its unique portrayal of the female subject.

Maryam Ghorbankarimi was born and raised in Tehran, Iran, and moved to Canada in 2001 to continue her education in film at Toronto’s Ryerson University. She completed her PhD in film studies at the University of Edinburgh in November 2012 and her dissertation was published as a book entitled A Colourful Presence; The Evolution of Women’s Representation in Iranian Cinema. As well as a scholar, Maryam is a filmmaker and has made some award-winning short films in both formats of short documentary and fiction. She also recently edited an Iranian-Canadian feature-length film entitled The Desert Fish. Her wider research interests include gender and representation and the concept of transnational cinema and culture. Her current research is on world cinema subjects, specifically the representation of sexuality and women in Middle Eastern cinema.

Email: [email protected]

******************************

Parviz Jahed, (film critic, journalist, filmmaker), PhD Candidate, University of St Andrews

Crime Thriller Elements in Bahram Bayzaie’s The Crow, Maybe Some Other Time and Mad Dog Killing,

The crime thriller is a film genre that offers a suspenseful account of a crime and is characterised by the moods evoked from this, giving the audience intensive feelings of suspense, excitement, surprise, anticipation and anxiety. Whereas the crime thriller film is a feature of almost all national cinemas, with many distinct takes on the form to be found in European, American and Far-Eastern cinemas such a Korean and Japanese cinema, it was not so prominent, however, within Iranian cinema and exceptionally rare in the pre-revolutionary period, making Bahram Beyzaie’s sophisticated forays into the genre particularly noteworthy. Much has been said and written about the mythical, metaphorical, ritual, philosophical, existential and feminist aspects of Beyzaie’s films. But in this paper I would like to discuss a lesser explored aspect of his cinema which is a representation of the criminal world and his utilisation of the main themes, elements and methods of the crime thriller genre such as suspense, tension, murders, captivities, rapes, kidnappings, investigations, revenge, the whodunit technique, plot twists, psychology, obsession, deathtraps, mistaken identity, false accusations and paranoia. By focusing on Beyzaie’s three films The Crow, Maybe Some Other Time and Mad Dog Killing, I would like to discuss how Beyzaie conveys his ideas about the mythical and philosophical through the framing device of the crime thriller plot and narrative structure. Pointing out and analysing the discreet yet highly conscious and pervasive influence of the genre.

Beyzaie is not a filmmaker whose films can be pigeonholed in a specific genre. He often exceeds the boundaries set by generic conventions and stereotypes. In the films that I’m focusing on in this paper, the director does not put crime at the centre of the plot, he applies some major elements of the crime thriller genre in these films that are dealing with their bewildered characters trapped in their prisonlike urban existences, searching for their purpose and identity within modern Tehran. Beyzaie’s stylistic thrillers are made with a Hitchcockian narrative style. By using the elements of suspense, paranoia and mystery, Beyzaie creates a tense and threatening world and exaggerates the menacing and haunting urban atmosphere where loyalty and safety hold no meaning and everybody is threatened. In Beyzaie’s thrillers, like Hitchcock’s, the protagonist (often a female character) is an innocent victim who is trapped in a strange, terrifying situation, in a case of mistaken identity or wrongful accusation. They face personal dilemmas along the way forcing them to make sacrifices for the sake of others. I will also illustrate the ways in which Bayzaie’s cinema goes beyond the expected Hitchcockian dramatic turns and suspenseful tropes and expectations the audience might have of the classic crime thriller and incorporates societal issues that the characters must face and relates their struggles to those faced by the ordinary populace of Iranian society.

Parviz Jahed is a film critic, journalist, filmmaker and lecturer in film studies, scriptwriting and film directing. He is the editor-in-chief of Cine-Eye (Cinema-Cheshm), a film journal focused on world cinema and independent films publishing in the UK. Jahed is also the editor of The Directory of World Cinema: Iran (Intellect, 2011). His book, Writing with a Camera (Nevashtan ba Dourbin), an in-depth interview with Ebrahim Golestan the veteran Iranian filmmaker and writer has been published in Iran in 2005. He has guest-edited a special issue of Film International journal focused on Iranian independent cinema (Intellect, January 2015). Jahed’s areas of research interest include Iranian Cinema (especially the new wave Iranian cinema and Filmfarsi), world cinema, French New Wave, and the history of film style and film theories. He also made a number of documentaries and short films including: Maria:24 hour peace picket, Ta’zieh, Another Naration, The Grass, The Lark, Day-break, Coffee-Cup Reading, Solayman Minassian:A Man With a Movie Camera and Bonjour Monsieur Ghaffari. Jahed has recently been working on his research project on the origins of the new wave in Iranian cinema at the University of St Andrews.

Email: [email protected]

***************************

Farshid Kazemi, PhD Candidate, University of Edinburgh

The Speaking Tree: The Mytho-poetics of the Female Voice in Bahram Beyzaie’s Cinema

In his Poetics of Myth, the Russian myth theorist Eleazar Meletinsky provides a number of semeiotic codes that undergird a particular articulation of mythopoeic discourse. In many of the cinematic works of Bahram Beyzaie, the leading female character(s) are represented through several different codes, often gesturing towards aspects of Iranian cosmogonic or creation myths. One such symbol or code structuring his strong female characters is the myth of the Speaking Tree mentioned in the Shahnameh or the Epic of Kings. The figure, which is called Vac/Vak, Vach or Vaq in the more ancient Indo-Iranian tradition, is the goddess (izad banu) of the word, speech, or voice and is related to the theme of creation, fertility and life. Indeed, this mytho-poetics of the voice is not only embodied in the strong and vocal female leads in Beyzaie’s cinema, but at times, it appears autonomous, disembodied. In this way the mytho-poetics of the female voice may be related to what Jacques Lacan termed the object-voice, and which Michel Chion designated as the acousmatic voice (acousmêtre) or the disembodied voice. It will be seen that although following the Judao-Christian-Islamic tradition, the acousmatic voice in the dominant cinema (i.e., Hollywood) is effectively a male voice, in the Indo-Iranian tradition it is a female voice. Thus, the mytho-poetics structuring the female voice in Beyzaie’s films subverts the patriarchal logic operative in Iranian cinema, by foregrounding female subjectivity, autonomy and agency. In this article, I will focus on a number of filmic examples such as, Gharibeh va Meh (The Stranger and the Fog, 1974), Charike-ye Tara (Ballad of Tara, 1979), Bashu, Gharibe-ye Koochak (Bashu, the Little Stranger, 1985), Shayad Vaghti Digar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Goft-o-gu ba Bad (Conversing with the Wind, 1998), Qali-ye Sokhangu (The Speaking Rug, 2006) all of which stage, in some form, this mytho-poetic heritage of the female voice in Beyzaie’s cinematic universe.

Farshid Kazemi is a Ph.D. candidate in the Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies department at the University of Edinburgh. He holds a B.A. in English Literature from the University of British Columbia. His dissertation project focuses on questions of gender, sexuality and desire in Post-revolutionary Iranian Cinema.

Email: [email protected]

****************************

Nina Khamsy, PhD Candidate in Film Studies, SOAS, University of London

Little Strangers: Representations of Displaced Youth in Iranian Films

This paper engages with a corpus of Iranian films representing encounters between Iranian and displaced youth – Iranian themselves, migrants or refugees, over the last three decades, to explore their alternative narratives to dominant discourses of national identity. As such, the paper will consider the relevance of these productions’ socio-political contexts, the filmmakers’ position in relation to their subject as well as their intended audience. It will then analyse several recurring themes in these films including spatial division, (mis)communication and language as means to divide and create oppositions between the main characters. By way of conclusion, the paper will argue that the intersectionality of ethnicity, social class and gender enables the characters to move beyond national differences and to offer a narrative of cultural diversity.

Nina Khamsy graduated from SOAS with an MA in Near and Middle Eastern Studies. She has specialised in the politics of Iranian Cinema in her MA and later on in her work at SOAS and in charities for Afghan refugees, where she organized masterclasses and led film screenings. As a research associate with Amir Kabir Institute, she is currently engaged in a group research on female pilgrimage in Mashhad, Iran. Her PhD research plan in Social Anthropology at Oxford University is focused on Afghan refugees in Iran and their migration trajectories to Europe.

Email: [email protected]

****************************

Fatemeh Khansalar, University of St Andrews

زبان طبیعت و زمین: خوانش بومگرایانه از غریبه و مه، چریکۀ تارا و باشو، غریبۀ کوچک

در این مقاله به سه فیلم روستایی بهرام بیضایی – غریبه و مه، چریکه تارا و باشو- پرداخته میشود تا نشان دهیم چگونه شخصیتهای اصلی این داستانها برای رسیدن به هماهنگی با طبیعت پیرامون خود در تعامل با آن قرار میگیرند. در این سه فیلم، بیضایی با همطراز قرار دادن طبیعت و انسان، مهمترین اصل نگاه بومگرایانه (اکوکریتیسیزم) را دراختیار بیننده میگذارد. برابریِ طبیعت و انسان، صدای سرکوبشدهی طبیعت را به او بازمیگرداند. به این ترتیب، انسان از جایگاه فاعل و قادر بلامنازع فرود میآید و در عرض طبیعت به مکالمه با او مینشیند. بیضایی با ترسیم سیمای زنان فیلمهایش – رعنا، تارا و نائي- نه تنها قدرت نادیده گرفته شدهی زنان را به آنها باز میگرداند بلکه با پیوند زدن آنها با طبیعت، محیط زیستِ پیرامون آدمی را که همواره به مثابهی زمینهی زندگی دیده شده است به متن میآورد و نشان میدهد که مکانهای فیزیکی مانند جنگل، رودخانه، کشتزار، دریا و غیره، جدایِ از مفاهیم استعاریِ معمول خود، مکانهایی واقعی هستند که در زندگی شخصیتهای فیلم حضوری ملموس دارند. این مقاله تلاش میکند تا نشان دهد که این رابطهی عادلانه و برابر میان انسان و طبیعت که در «غریبه و مه» آغاز میشود، در تارا توسعه مییابد و در «باشو» به بلوغ خود میرسد. به این ترتیب «نائی» و «باشو» سویههای پنهان طبیعت را میبینند، او را مخاطب قرار میدهند و در هماهنگی کامل با او درمیآیند

The Language of Nature and Earth: An Eco-critical Reading of The Stranger and the Fog, Ballad of Tara, and Basho, the Little Stranger

In this article, three feature films of Bahram Beyzaei are analysed to show how the main characters confront nature and converse with it in order to live in harmony with their environment. In these films, humankind loses his position as the main subject of the world and becomes capable of interacting with their environment. By empowering his female characters – Ra’na, Tara, and Naei – and weaving them into the texture of nature, Beyzaie foregrounds nature as a major character. In these village films, physical places such as forests, rivers, farms and the sea in addition to providing the essential elements of setting and having occasional metaphorical implications, become a force through which the lives of the individuals becomes meaningful. This article is an attempt to illustrate that the equality between human beings and nature, which was originally established in The Stranger and the Fog, develops further in Ballad of Tara, and reaches maturity in Basho, the Little Stranger. Thus Naei and Basho become capable of having dialogue with nature and ultimately achieve a complete harmony with it.

Fatemeh Khansalar Fatemeh Khansalar was born in Shiraz and holds a BSc in Botany from the University of Isfahan and an M. Litt. in Middle Eastern Literary and Cultural Studies from the University of St Andrews. In 1999, she joined Rooyesh Institute of Art, Culture and Foreign Languages as deputy-manager, an appointment that continued for 10 years. While in the post, she ran several art exhibitions, conferences and seminars, including the first-ever conference on ‘Naghashan-e Gha-hveh-Khanei’, or ‘Iranian Cafe-house Painting’. In 1999, she was invited to join the editorial board of Zendeh-rood, a prestigious quarterly literary magazine in Iran, where she is still a member. She has also served as the production manager and a member of the editorial board of Mehraveh magazine, another quarterly periodical in art and literature, from 2003 to 2009. She has published a collection of short stories in 2002, and also several short stories and literary articles in Zendeh-rood, Asr-e Panjshanbeh, and Mehraveh periodicals. Her second short story collection is also soon to be published. After moving to Scotland in 2009, she has run a workshop for Persian miniature painting on a weekly basis. She is currently working on her novel, ‘Herala’, as well as her research on ‘Narrative Identity’ in works and life of Houshang Golshiri.”

Email: [email protected]

****************************

The Dialogue of Beyzaie’s Downpour with Iranian Cinema: Intellectuality, Masculinity and Marginality

This paper examines the meta-filmic dialogue that Beyzaie’s Downpour opens with Iranian cinema to establish the necessity of introducing new types of heroes and subjects. This dialogue is meta-filmic because the film contains many instances of conscious theatricality and framing which highlight the power of cinema to shape dreams and fashion contemporary identities by providing role models. It turns cinema into one of its major subjects by reversing and challenging the images of ‘the tough guy hero’ and ‘the benevolent official’ who were at the centre of Iranian cinema in the 1950s and 1960s. Thus enters Hekmati, as a stranger, into Iranian cinema and into a traditional neighborhood, to establish his position in competition with two towering embodiments of hegemonic masculinity, Aqa Rahim and the Headmaster. This meta-filmic dialogue, however, is not just about Hekmati, the constructive intellectual, because along with this new figure enter a host of other marginalized characters: six women with different types of dreams and fears, and a host of children characterized by non-conformist agencies and potential for change, which may promise a better future if the forces of hegemonic masculinity and surveillance allow it. With its comic undertone and its unique aesthetics, the film opened new filmic horizons for undermining the machinations of hegemonic masculinity, which has since time immemorial guaranteed the continuation of inherited violence and celebrated masculinity above all in the sense of an ability to destroy.

Saeed Talajooy is lecturer in Persian Literature at the School of Modern Languages, University of St Andrews. Saeed has taught and published on literature, drama and cinema in Iran and the UK, and is currently teaching comparative literature and Persian literature modules. His research is on the point of convergence between cultural theory and literature, performance and film and on the reflections of the changing patterns of Iranian identities in Persian literature and Iranian theatre and cinema. It involves analysing the works of Iranian poets, novelists, playwrights and filmmakers to find how they refashion indigenous forms and characters or adapt Iranian or non-Iranian myths, history and literary narratives, to challenge dominant political and cultural discourses. Another aspect of his research involves comparative studies of cultural resistance in Africa and the Middle East. His publications include several articles on Iranian theatre and cinema, a co-edited volume entitled Resistance in Contemporary Middle Eastern Studies: Literature, Cinema and Music (Routledge 2012) and a special issue of Iranian Studies on Bahram Beyzaie. He is currently working on a monograph entitled The Cinema and Theatre of Bahram Beyzaie.

Email: [email protected]

****************************

Farshad Zaehdi (PhD), Lecturer, University Carlos III de Madrid

Exploring the cinema of Bahram Beyzaie: space, time, bodies, and memory

Bahram Beyzaie is not just a filmmaker. He is a myth. A mythologist who became a myth because of the broad resonance of his work in Iranian socio-political realm. Widely recognised as a great master for the Iranian cinephilia, he never achieved a similar recognition by the international critics. Maybe because his style has not been so revolutionary for European observers, or maybe his works has been based on a sophisticated linguistic structure which is doomed to be lost in translation. Who is Bahram Beyzaie? Finding an answer for this question needs a greater space and time, but what we seek here is to find an answer to who Bahram Beyzaie is as a filmmaker? In other words, while a study of personality of the author needs a great knowledge of his oeuvres, from his academic researches on myth and history to his creative works in literature, theatre, and cinema, here what we try to define and analyse is his cinematic aesthetic. But what is exactly the cinematic aesthetic? This is the first question to which we have to find an answer. A film is not just an entertainment medium, but a dispositive which shows its creator’s desires and provides us spectators how to desire. A film never is capable to show us the ultimate sense of reality, but the truth precisely resides in its very failure on mapping the reality. This is maybe the crucial issue to approach Beyzaie’s films. Whereas generally the critics and scholars define Beyzaie’s cinema as a discursive social criticism, and try to find similarities between outer realities and the movies’ diegetic realism, it has been neglected the very subjective vision of the author to depict his illusionary world. In short, we have preferred to see the social realities through Beyzaie’s films, and not to interpret the truth which has been structured by the very failure of reflecting the reality. In this regard, the first aim of this work will be an introduction to how Beyzaie’s films explore the space and bodies to materialize the author’s ideas and thoughts. The questions therefore arise here are: how Beyzaie’s films deal with memory and, in a broader sense, how they address the preoccupation of the author with history? This question pave the way for the next one: how they depict inner spaces of homes, offices, shops, cafés, etc. and outside spaces such as, cities, streets, and of course the semi-private spaces like cars and building sites. Additionally, how the Beyzaie’s films deal with the realism? In regard to this, we should study the formal aspects of the author’s style: his shot planning and editing. If the cinema is primarily an audio-visual art and an extension of the spectator sight and hearing, therefore we can explore the point of view shots of Beyzaie’s works and its soundscapes in order to find how his characters see and hear the world. Finally, the ideal question toward a conclusion must be: is Bahram Beyzaie a modern filmmaker? And if so, what is exactly the modernity in his style.

Farshad Zahedi received his Ph.D. in History of Cinema in 2008. At present he as a senior lecturer teaches Moving Image History and Film Studies at University of Carlos III de Madrid. He is Associate Member of Centre for Iranian Studies at SOAS (University of London) and member of research project of Childhood and Nation in World Cinema. In recent years he has published widely about his research interests: Iranian cinema and cultural studies; aesthetic roots and gender representations. Among his publishing stands out “Myth of Bastoor and Children of Iranian Independent Cinema” Film International. vol. 12, n. 3. pp. 21-30, 40 años de cine iraní: el caso de Dariush Mehryui [40 years of Iranian cinema: The case of Dariush Mehrjui], Madrid, Fragua: 2010 and “Irán, cine y modernidad” [Iran, Cinema and Modernity], Revista de Occidente, n. 343, 2009, pp. 33-53.

Email: [email protected]

****************************

Reza Zarghamee, author and PhD Candidate, University of St Andrews

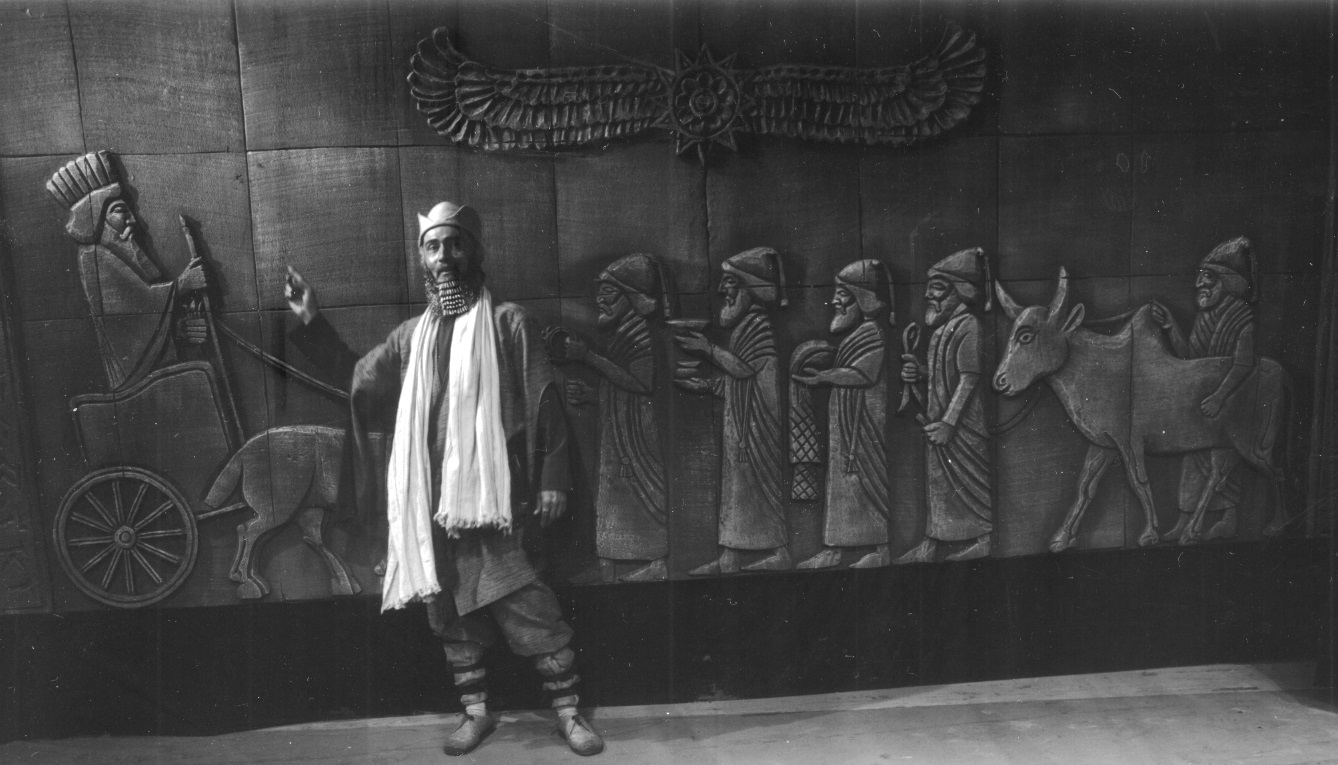

Darius the Dragon-Slayer

Abstract: The concept of cultural production covers, among other things, the reinforcement of age-old cultural values and beliefs, as well as the interpretation of contemporary events in terms of traditional ideals. This paper explores how the popular accounts of the rise to power of the Achaemenid Persian emperor Darius I (reigned 522–486 bce) constituted a form of cultural production, inasmuch as these accounts were modeled after a well-known Iranian myth and, in turn, seem to have influenced the development of this myth into legend in the Iranian epics. The reformulation of this myth, which involves the well-known characters known in Avestan as Yima (New Persian Jam, Jamshid), Thraetona (Fereydun), and Azhi Dahaka (Zahhak), is a hallmark of several of Mr. Bahram Bayzaie’s plays.

Reza Zarghamee is a graduate of Harvard Law School (J.D. 2003) and Columbia University (B.A. 2000), where he majored in Biology and Ancient History, with an emphasis on past and present Persian languages and civilization. He has been a Doctoral Fellow at St. Andrews University since 2015, where his work is focused on the interactions between historiography and folklore in ancient Iran.

Email: [email protected]

****************************

Saeed Zeydabadi-Nejad, Lecturer of Media and Film, SOAS, University of London

Language of others vs othering of languages: Bashu and multilinguality in Iranian cinema

Inclusion of languages other than Persian has become commonplace in Iranian films particularly since the turn of the century with some films being entirely in a regional language. Comparing Che (Hatamikia 2014) with the pioneering Bashu, the Little Stranger (Beyzaie 1985), the paper focuses on the two films’ different approaches to multilinguality. The films are also comparable because of armed conflicts with external and internal ‘enemies’ being central to their plots. This paper argues that while Che uses Kurdish language as means of othering the Kurds in tandum with the armed conflict, in Bashu the inclusion of languages other than standard Persian works to the opposite effect of decentring Persian speaking Iranians. The paper concludes that in spite of commonness of multilinguality in Iranian films nowadays, Bashu, the Little Stanger remains unique in its approach.

Saeed Zeydabadi-Nejad has been lecturing at SOAS, University of London, on film and media since 2004, has done consultancy work for BBC World Service, and has lectured at the Institute of Ismaili Studies on a joint degree awarded by University College London. Saeed has a PhD from SOAS. He has authored The Politics of Iranian Cinema (2010) based on ethnographic fieldwork. His publications include “Watching the forbidden: reception of banned films in Iran” in The State of Post-Cinema (Hagener et al. 2016). His media appearances include radio and TV programmes on BBC Radio Three and Four as well as BBC World Service.

Email: [email protected]

****************************

The workshop has been funded by the British Institute of Persian Studies, the Honeyman Foundation, School of Modern Languages (University of St Andrews), and Institute of Iranian Studies (University of St Andrews).

The Honeyman foundation was established by the generosity of A.M. (Sandy) Honeyman, a former Professor in the University of St Andrews in 1985 with the aim of encouraging education and research in general and study of Middle Eastern languages and cultures, in particular.